Brilho e coragem: Encontrando esperança através da arte e da fibrose cística

Durante o Mês da Consciencialização da FC, a Emily's Entourage convida membros da comunidade da fibrose cística (FC) a partilharem as suas histórias. O post de hoje apresenta Dylan Mortimer - um artista e recetor de um transplante duplo de pulmão que utiliza arte arrojada e coberta de purpurinas para partilhar o seu percurso e dar esperança a outras pessoas com FC.

Nasci em 1979 e foi-me diagnosticada fibrose cística (FC) aos três meses de idade. Naquela altura, havia muito pouca esperança em relação à doença; o futuro de alguém como eu era, na melhor das hipóteses, incerto. No entanto, consegui desafiar as probabilidades durante a minha infância, acabando por me formar na faculdade, apaixonar-me, casar e até constituir família como pai de dois filhos.

Mas, com cada marco pessoal alcançado, a minha função pulmonar continuava a deteriorar-se. Tentei manter a esperança de que as terapias direcionadas para as mutações fossem aprovadas em breve, mas os meus pulmões estavam demasiado marcados e danificados. Em 2017, aos 37 anos, fui submetido a um transplante duplo de pulmão.

Mas, com cada marco pessoal alcançado, a minha função pulmonar continuava a deteriorar-se. Tentei manter a esperança de que as terapias direcionadas para as mutações fossem aprovadas em breve, mas os meus pulmões estavam demasiado marcados e danificados. Em 2017, aos 37 anos, fui submetido a um transplante duplo de pulmão.

Durante um breve período, as coisas pareceram prometedoras, até que, apenas 18 meses depois, entrei em rejeição, quando o nosso corpo ataca o novo pulmão como um corpo estranho. A minha única opção era submeter-me a uma segundo transplante duplo de pulmão, mas devido aos anticorpos que se desenvolveram com o meu primeiro transplante de pulmão, as minhas hipóteses de encontrar um dador compatível eram praticamente inexistentes.

Quando me encontrava na lista de transplantes mais uma vez, enfrentando o que pareciam ser probabilidades insuperáveis, as terapias direcionadas para a mutação que eu tanto esperava foram finalmente aprovadas. Vi imagens de outras pessoas com FC de todo o mundo a celebrar a sua nova vida e a sua nova saúde.

Fiquei feliz por eles! Mas por dentro, estava destroçada.

As terapias pelas quais tinha esperado e lutado tanto para beneficiar tinham chegado demasiado tarde para mim. O meu corpo já tinha sofrido demasiado. Tinha perdido a oportunidade. O desespero era esmagador.

Mesmo assim, mantive a esperança em mim.

Depois - algo milagroso aconteceu. Uma mulher que seguia o meu percurso no Instagram viu a minha história. O primo dela tinha acabado de falecer e a família estava a tentar honrar a vida dele através da doação de órgãos. Ela contactou-me, sem sequer saber se seríamos compatíveis.

Uma hipótese num milhão. E de alguma forma... estávamos.

Fui transplantado uma segunda vez em 2019, ressuscitado mais uma vez da morte.

Essa experiência não mudou apenas a minha vida. Mudou a forma como eu contada a minha vida.

A arte sempre fez parte de mim. Desde muito jovem, senti-me atraído pela criação - estudei arte na faculdade e fui para a escola de pós-graduação em Nova Iorque para continuar. Ao longo dos anos, trabalhei numa grande variedade de meios, desde escultura a pintura e até colagem. Mas até ter sido selecionada para o meu primeiro transplante, nunca tinha utilizado a arte para explorar ou expressar o meu percurso de saúde.

A arte sempre fez parte de mim. Desde muito jovem, senti-me atraído pela criação - estudei arte na faculdade e fui para a escola de pós-graduação em Nova Iorque para continuar. Ao longo dos anos, trabalhei numa grande variedade de meios, desde escultura a pintura e até colagem. Mas até ter sido selecionada para o meu primeiro transplante, nunca tinha utilizado a arte para explorar ou expressar o meu percurso de saúde.

Demorou algum tempo a reconciliar essa parte da minha vida, mas assim que o fiz, a arte tornou-se mais do que uma saída criativa - tornou-se a minha voz, a minha forma de partilhar o indizível, de inspirar e de oferecer esperança a outros que navegam nos capítulos mais difíceis das suas próprias histórias.

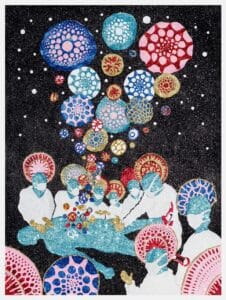

Os símbolos do meu trabalho artístico são retirados diretamente da minha experiência: cicatrizes, células, sacos de soro, ambulâncias, quartos de hospital - os marcadores físicos e emocionais de uma vida passada a lutar para respirar. Embora todas estas coisas sejam muito traumáticas, são também simultaneamente as coisas que me salvaram. A batalha e a tábua de salvação.

De todos os materiais que podia utilizar para renderizar estes objectos, optei por banhá-los em purpurina - e não um pouco, mas sim completamente cobertos, sem desculpas, por este material brilhante! A purpurina é confusa. É invasivo. Agarra-se a tudo e espalha-se como uma doença. Pode mesmo irritar as pessoas, tal como uma doença. E, no entanto, é transformador e belo. Apanha a luz. Exige atenção. Transforma o vulgar - e até o doloroso - em algo inegavelmente belo. Dessa forma, reflecte as nossas histórias de sobrevivência, de resiliência, de recuperação de algo radiante dos destroços da doença.

Quero que o meu trabalho artístico seja um recipiente que transforma situações aparentemente sem esperança em pinturas e colagens que são agressivamente alegres e agressivamente esperançosas.

Porque é esse o tipo de esperança que é preciso para sobreviver quando as probabilidades estão contra nós. Não é silenciosa ou passiva. É feroz e teimosamente brilhante em face da escuridão. Esse tipo de esperança é o que me tem levado através de uma vida que, no papel, não deveria ter sido assim.

Quando eu nasci, a esperança média de vida de uma pessoa com FC era de cerca de 14 anos. Não havia muitas perspectivas, muito menos sonhos de vida adulta, casamento ou paternidade. Mas aqui estou eu - agora com 45 anos, 20 anos de casado, com dois filhos incríveis de 16 e 14 anos. E, no ano passado, corri a maratona de Nova Iorque. Que bênção estar vivo!

Quando eu nasci, a esperança média de vida de uma pessoa com FC era de cerca de 14 anos. Não havia muitas perspectivas, muito menos sonhos de vida adulta, casamento ou paternidade. Mas aqui estou eu - agora com 45 anos, 20 anos de casado, com dois filhos incríveis de 16 e 14 anos. E, no ano passado, corri a maratona de Nova Iorque. Que bênção estar vivo!

Chegámos tão longe nesta corrida contra a FC, mas ainda temos muito que andar.

Tudo o que conquistei aconteceu apesar de não recebem terapias dirigidas a mutações a tempo de evitar o transplante. Embora haja agora mais esperança do que nunca para os jovens com FC, ainda há muitos que não podem beneficiar das terapias dirigidas às mutações. Luto e espero por eles, tal como muitos lutaram por mim e me deram esperança.

É isso que se passa com a nossa fantástica comunidade de FC - estamos no negócio de dar esperança aos que não têm esperança. Tal como encharcar verdades difíceis em purpurina, iluminamos a dignidade, a resiliência e o brilho inesperado que vive até nos momentos mais negros. Avançamos - não apenas por nós próprios, mas por aqueles que ainda estão à espera, que ainda precisam de ajuda. E continuaremos a avançar - de forma corajosa, criativa e cheia de esperança - até que todas as pessoas tenham acesso às terapias que salvam vidas e aos futuros que merecem.

Autor

Artista e pessoa que vive com fibrose cística, Dylan Mortimer formou-se com um BFA no Kansas City Art Institute e um MFA na School of Visual Arts em Nova Iorque. O seu historial de exposições inclui a Universidade do Sul da Califórnia, o Seminário Teológico de Dallas, a Haw Contemporary e a Universidade de Columbia. Criou também instalações de arte pública em várias cidades, incluindo Nova Iorque, Chicago, Baltimore, Kansas City e Denver. Ele e a sua mulher Shannon têm dois filhos e vivem em Los Angeles.

Saiba mais sobre o seu trabalho visitando o seu sítio Web aqui.